The Role of Probability in Value Betting

This article examines how probability is used within value betting as a descriptive and analytical concept rather than a predictive one.

Drawing on long-term experience across football, basketball, and tennis markets, it explains why individual results remain unpredictable and why probability is best understood through averages, distributions, and long-run behavior.

The focus is on clarifying common misconceptions around odds, expected value, and variance, and on showing how probability models help frame uncertainty instead of forecasting outcomes.

Why Probability Matters More In Betting Than Outcomes

I have been working with value betting concepts since 2013, both in pre-match and live markets, across sports like football, basketball, and tennis. Over the years, one lesson has remained consistent regardless of sport, league, or market type: individual outcomes are unpredictable, but probability helps describe patterns over time.

Probability is often misunderstood in sports betting. It is not a prediction tool, and it is not a promise of a specific result. Instead, probability is used to describe likelihoods and model expectations across a large number of events. A single match, point, or possession can always produce an unexpected outcome, even when the underlying assumptions appear sound.

This is why focusing on isolated wins or losses can be misleading. Short-term results are influenced by randomness, timing, and variance, none of which probability is designed to eliminate.

Probability does not determine what will happen next; it helps explain what tends to happen on average when similar situations are observed repeatedly.

In value betting, probability plays a descriptive role rather than a predictive one. It provides a framework for comparing expectations over many trials, not a guarantee of success in any individual event.

Understanding this distinction is essential for interpreting betting models responsibly and for avoiding common misconceptions about certainty, control, and short-term performance.

This article explores how probability functions within value betting, why it should be viewed as a long-run analytical tool, and why outcomes alone are a poor measure of whether a probability-based approach is being applied correctly.

What Probability Means in a Betting Context

In a betting context, probability is a numerical way to express how likely an outcome is, usually represented on a scale from 0 to 1, or as a percentage from 0% to 100%. A probability of 0 means an outcome is considered impossible, while a probability of 1 means it is considered certain. Most real-world sports events fall somewhere between these two extremes.

It is important to distinguish between different types of probability commonly referenced in betting discussions:

Theoretical probability is based on mathematical models or historical assumptions, often derived from large datasets or simplified conditions. It represents how often an outcome would occur under idealized or repeatable circumstances.

Implied probability is derived directly from betting odds. When odds are converted into probability, they reflect how the market prices an outcome, including adjustments for margins and market dynamics. Implied probability describes pricing, not objective truth.

Estimated probability is an attempt to approximate the likelihood of an outcome using available information, such as statistics, context, or modeling assumptions. These estimates vary between analysts and are influenced by data quality and methodology.

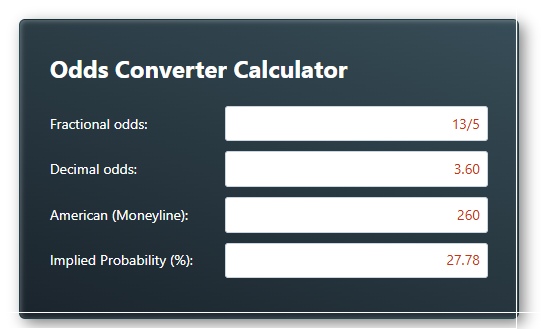

Implied Probability and Odds

Betting odds can be translated into implied probability.

This conversion shows how likely an outcome is priced by the market.

For decimal odds, the implied probability is calculated as:

Implied Probability = 1 ÷ Decimal Odds

For example, decimal odds of 2.00 imply a probability of 50%.

Odds of 1.50 imply a probability of about 66.7%.

Implied probability reflects how outcomes are priced, not how often they will occur.

It is a market-based estimate, not an objective measurement.

Bookmakers include a margin in their odds.

Because of this margin, the total implied probability of all outcomes usually exceeds 100%.

This built-in difference means implied probability is not the same as true probability.

It represents pricing assumptions rather than real-world likelihood.

Understanding how odds translate into probabilities helps explain how betting markets function.

It also provides context for tools such as odds converters and expected value calculators, which are used to analyze pricing structures rather than predict outcomes.

The Role of Variance in Probability-Based Strategies

Probability helps describe likelihoods, but it does not smooth real-world results.

Even when probabilities are favorable on average, outcomes remain uneven.

Losing streaks are a normal consequence of randomness.

They can occur even when the underlying statistical expectation remains unchanged.

Outcomes also tend to cluster.

Wins and losses do not alternate in an orderly way, but often appear in runs that feel counterintuitive.

This behavior is a natural property of random processes.

It does not mean the probability model is wrong, only that short sequences can deviate strongly from averages.

Variance becomes more visible when odds are higher, sample sizes are smaller, or when results are observed over limited time frames.

In these conditions, fluctuations dominate perception.

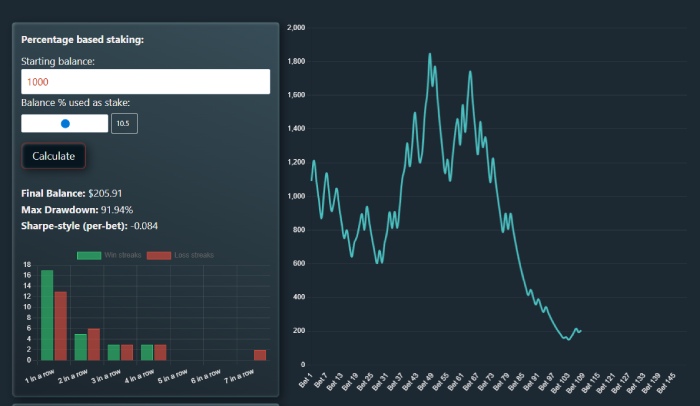

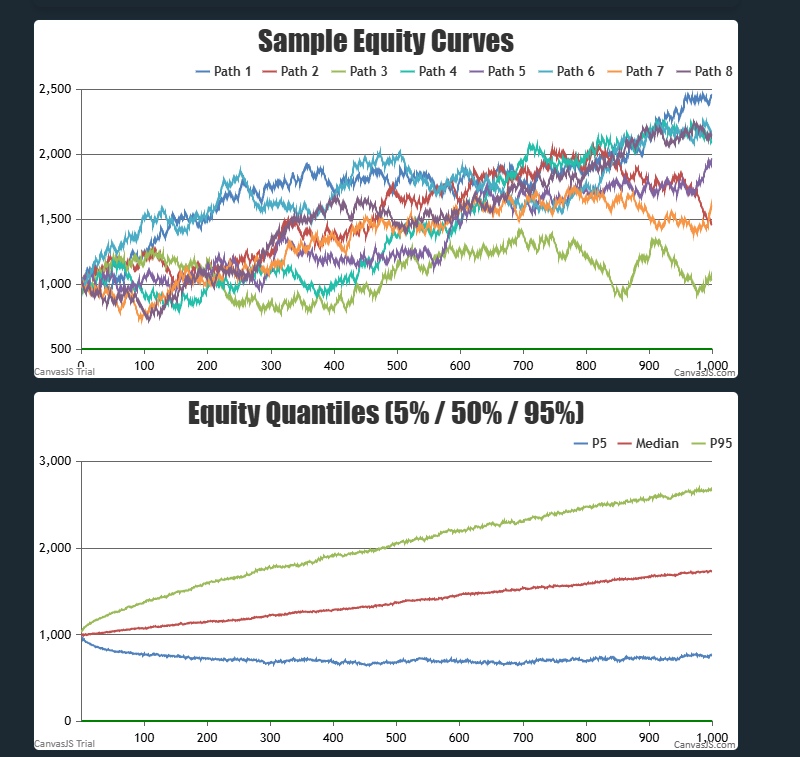

To better understand this effect, simulations can be useful.

A value betting simulator models many possible paths by varying inputs such as number of bets, odds dispersion, estimated edge, staking method, and randomness.

By running thousands of simulated trials, tools like our betting simulator which helps visualize how identical assumptions can still lead to very different outcomes.

The purpose of such simulations is not prediction.

They are designed to illustrate variance, drawdowns, and distribution of results, reinforcing why probability describes long-run behavior rather than short-term certainty.

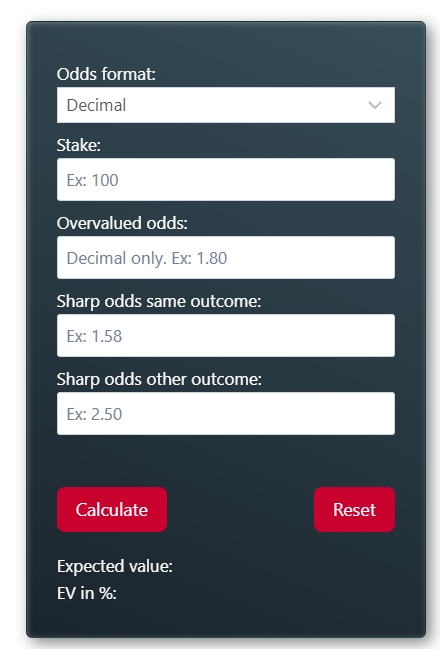

Expected Value as a Probability-Based Concept

Expected value is often misunderstood because it is expressed as a single number.

In reality, EV represents an average theoretical outcome across a large number of similar situations.

It does not describe what will happen on any single bet.

It also does not imply that short-term results will follow the expectation.

I experienced this clearly while live betting on basketball quarters.

There were situations where odds around 1.90 implied a much lower likelihood than my estimated probability, which was well above 70%.

From a statistical perspective, the expectation was favorable.

Yet many of those individual bets still lost.

This happens because EV is a statistical expectation, not a guarantee.

Variance can dominate outcomes over short and even medium sample sizes.

Even when the estimated probability is high, randomness still plays a major role.

Single results can deviate significantly from the average theoretical outcome.

This is why EV should be understood as a modeling concept.

It helps describe expected behavior over many repetitions, not predict or secure individual results.

Probability Models and Real-World Market Limits in Betting

Probability models are built using assumptions, historical data, and simplified conditions.

Real-world betting markets, however, are not static.

Odds change as new information becomes available.

Injuries, lineup changes, weather, and market participation all influence pricing through continuous information flow.

Because of this, probability estimates can lose relevance over time.

Models that were accurate under one set of conditions may become less representative as market dynamics evolve.

This is why probability modeling is an adaptive process.

Estimates need to be reviewed, adjusted, and interpreted within the context of current conditions rather than treated as fixed values.

At the same time, probability alone is not enough to describe real outcomes.

Execution risk plays a role, especially when timing, liquidity, or price movement affect decision-making.

Psychological factors also matter.

Biases such as overconfidence, recency bias, or loss aversion can influence how probabilities are interpreted and acted upon.

Bankroll constraints impose practical limits.

Even sound probabilistic reasoning cannot remove the impact of capital size or drawdown tolerance.

Finally, structural limits exist within markets themselves.

Rules, margins, and operational constraints shape outcomes in ways that probability models cannot fully capture.

Together, these factors highlight why probability should be viewed as a framework for understanding uncertainty, not as a standalone solution.

Tools That Help Visualize Probability in Value Betting

Probability concepts are often easier to understand when they are visualized rather than described in abstract terms.

For this reason, analytical tools such as calculators, simulators, and visualizers can be useful in an educational context.

These tools do not forecast future outcomes or indicate what will happen next.

Instead, they illustrate distributions, ranges, and possible paths based on mathematical inputs and assumptions.

For example, an odds converter can help translate prices into implied likelihoods, making it easier to compare formats and understand how markets express probability.

An expected value calculator can show how different assumptions affect statistical expectation, without implying certainty or performance.

A value betting simulator can model variance and dispersion over many simulated trials, highlighting how outcomes can differ widely even when inputs remain the same.

It’s important to treat these tools as explanatory aids.

They are designed to support understanding of probability and uncertainty, not to provide predictions or guarantees about real-world results.

Conclusion

After many years of working with probability-based approaches in sports betting, one lesson has remained consistent: probability describes tendencies, not outcomes.

It helps frame what might happen across a large number of trials, but it does not determine what will happen next.

Throughout my own experience with value-based methods in basketball, tennis, and football, there were extended periods where results moved sharply against expectations.

Even when placing bets that aligned with positive statistical assumptions, I experienced long stretches of unfavorable outcomes, sometimes lasting weeks.

These periods were not exceptions—they were part of the normal variance that probability models cannot smooth out.

This is why probability should be approached with humility.

It is a way to model uncertainty, not to eliminate it.

Short-term results remain unpredictable, psychological pressure can distort decision-making, and risk is always present, regardless of how sound a model appears on paper.

Used correctly, probability supports better understanding of uncertainty and risk exposure.

Used incorrectly, it can create false confidence.

Recognizing this distinction is essential for anyone engaging with probability-based analysis in sports betting or any other uncertain environment.

Sources: